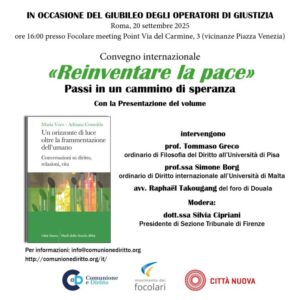

Conference organised by Communion & Law on the occasion of the Jubilee Year of Justice, entitled: “Reinventing Peace – Steps forward in a journey of hope”.

by Prof. Simone Borg

This address, delivered at the seminar “Re-inventare la Pace – Passi in un Cammino di Speranza” (Reinventing Peace – Steps forward in a journey of hope) and the launch of the book Un’Orizzonte di Luce oltre la Frammentazione dell’Umano: Conversazioni su Diritto, Relazione e Vita, explores the evolving role of law in society, the interplay between individual and collective rights, and the necessity for peace-oriented multilateralism rooted in people’s participation. Drawing on personal, professional, and academic insights, especially the legacy of Maria Voce and Prof Adriana Cosseddu, Prof Simone Borg examines how law, when centred on relationships and fraternity, can be a beacon of hope and justice in a fragmented world.

This address, delivered at the seminar “Re-inventare la Pace – Passi in un Cammino di Speranza” (Reinventing Peace – Steps forward in a journey of hope) and the launch of the book Un’Orizzonte di Luce oltre la Frammentazione dell’Umano: Conversazioni su Diritto, Relazione e Vita, explores the evolving role of law in society, the interplay between individual and collective rights, and the necessity for peace-oriented multilateralism rooted in people’s participation. Drawing on personal, professional, and academic insights, especially the legacy of Maria Voce and Prof Adriana Cosseddu, Prof Simone Borg examines how law, when centred on relationships and fraternity, can be a beacon of hope and justice in a fragmented world.

The book’s chapters are organised around themes that scrutinise the function of law in contemporary society, tackling both enduring and emerging challenges. A central element is the inclusion of candid dialogues conducted by Maria Voce, engaging with politicians, academics, civil society, and young people across different regions. These dialogues begin with the fundamental question, “what is law?”, and traverse its purpose, philosophy, and the pitfalls of legal fragmentation—especially when lawmakers neglect the balance between individual and collective rights.

Prof Simone Borg, explained how as a Maltese lawyer she studied and worked with a legal system based upon Roman Law, which is renowned for its simplicity. During her career, she noticed the evolution of straightforward norms to an increasingly complex and super specialised body of law. Despite this proliferation, the speaker asserts that it is the quality, not the quantity, of laws that underpins an effective rule of law. An abundance of legislation does not guarantee justice or the proper functioning of society.

Prof Simone Borg, explained how as a Maltese lawyer she studied and worked with a legal system based upon Roman Law, which is renowned for its simplicity. During her career, she noticed the evolution of straightforward norms to an increasingly complex and super specialised body of law. Despite this proliferation, the speaker asserts that it is the quality, not the quantity, of laws that underpins an effective rule of law. An abundance of legislation does not guarantee justice or the proper functioning of society.

She argues that in fact the contributors to Un’Orizzonte di Luce question whether the sheer volume of legal norms enhances or diminishes the law’s efficacy. They examine whether the plurality of laws—reflecting diverse cultures and traditions—provides substance, procedural fairness, and effective governance. The book’s strength she argues, lies in its range of perspectives, with contributors from various backgrounds considering legal topics of universal significance. This diversity underscores the fundamental question: is law merely a system of legislation and enforcement, or does it serve a greater purpose for humanity?

Despite this diversity, a unifying thread runs through the book: the law’s true purpose (ratio legis) is not simply to impose limits, but to foster relationships and trust. The prevailing view is that a restrictive interpretation of law’s purpose leads to disillusionment and a failure to secure peace and justice, even as laws multiply. True well-being—both private and public—requires law to transcend mere order and punishment, and instead to unlock its potential to construct meaningful relationships, from individuals to the international community. Law, in this vision, is a tool for peace, security, and well-being.

Despite this diversity, a unifying thread runs through the book: the law’s true purpose (ratio legis) is not simply to impose limits, but to foster relationships and trust. The prevailing view is that a restrictive interpretation of law’s purpose leads to disillusionment and a failure to secure peace and justice, even as laws multiply. True well-being—both private and public—requires law to transcend mere order and punishment, and instead to unlock its potential to construct meaningful relationships, from individuals to the international community. Law, in this vision, is a tool for peace, security, and well-being.

This innovative approach is inspired by the experiences of Maria Voce and Adriana Cosseddu with the Focolare Movement, founded by Chiara Lubich. The “Focolare”, meaning the hearth, symbolises nurturing relationships for the benefit of all. Legal practice, when illuminated by Gospel values, prompts a re-examination of the ultimate role of law—and indeed any discipline—as a means to generate life and respond creatively to adversity.

The book validates the law as a social science from a relational perspective. Contributors ask whether law is currently fulfilling its role as the medium for nurturing relationships, particularly in protecting the vulnerable. Law should be an instrument of enlightenment, ensuring dignity, justice, peace, and security at both national and international levels. Relationships are seen as an endowment, binding human beings as members of society and stewards of the planet. The book’s outlook is future-oriented, as seen in its engagement with young people and institutions like the United Nations.

Prof Borg argues that the message in the book is consistent throughout: law must be a conduit for fraternal relationships, overcoming conflicting interests and barriers to peace at all levels. Legal systems that facilitate fair, equitable relationships can foster global coexistence and societal well-being.

The classic maxim “Ibi Societas ibi Jus” (where there is society there is law) can be recast as “Ibi Homo ibi Jus” (where there is humanity there is Law). Individual and community rights are interdependent; law’s mission is to guarantee that no one is left behind, allowing all to participate equally in society. Rights should not compete, but coexist in a reciprocal relationship, the foundation of a just and inclusive society.

The book also addresses the proliferation of laws in response to conflict resolution, constitutional rights, and new legal complexities—ranging from environmental crises and data protection to artificial intelligence and the digital society. Law-making is often the default response to threats to dignity and liberty, but the book argues for a clear delineation of responsibilities and for institutions that foster integration in a multicultural society, promoting peace.

Institutional encounters are proposed to nurture a juridical culture of peace, tolerance, and reconciliation, warning against the uncritical delegation of legal responsibility to technology. While technology can be positive, its use must be underpinned by legal frameworks that guarantee accessibility and safety, ensuring it serves humanity.

Prof Borg then shares her personal professional experience, reflecting on the question whether international law and multilateralism serve governments or the people. Multilateralism, often seen as a challenge to national interests, is reimagined as a force for humanity, not just statecraft. She argues that the preamble of the United Nations Charter — “We the peoples of the United Nations determined…”—is highlighted as a deliberate emphasis on people’s agency in multilateralism. The Charter enshrined the choice of multilateralism over unilateralism, aiming to “practice tolerance and live together in peace”, with multilateralism by and for the people as the path to these goals.

Multilateralism’s democratic core is its inclusion of diverse voices—civil society, communities, and public consultation are now integral to multilateral debates. At the UN, civil society’s role in high-level dialogues exemplifies progress towards peace. Diplomacy, traditionally the preserve of states, now increasingly values the participation of non-state actors, especially in tackling global challenges like climate change. For example, the International Court of Justice’s recent advisory opinion affirms that protecting the climate is an “erga omnes” obligation—owed to all of humanity, present and future.

Law should aim to foster also responsibility among people and not just rights. Prof Borg argues that when people stand up to demand a change, like the call for climate justice coming from the grass roots for example, the same people clamouring for such a noble cause must ask themselves the question: how can I change to fulfil my duty towards climate justice? Civil society’s engagement would be truly credible and a game changer, when we as citizens shoulder the responsibility as individual citizens, leading by example and acknowledge the need to change our behaviour to achieve climate justice. Only such a recognition of the concomitant obligation to a claim of a rights, can ward off populist governments, which cite “national” interest to oppose essential reforms to achieve climate justice, essential for humanity’s very survival.

The dialogues throughout the book propose the human family—fraternity—as the horizon for law’s ultimate goal: a just society. When fraternity is used as the yardstick for assessing legal systems, law can truly instill freedom and equality. Prof Borg concluded by explaining that the book offers a way forward, encouraging lawmakers and practitioners to reappraise their vocation as guardians of social conscience and inspiring citizens to recognise their role in upholding justice. The rule of law depends not only on legislation but also on the commitment of all—law-makers, practitioners, and citizens—to anchor freedom and equality in human fraternity, for present and future generations, and for the planet itself.

Malti

Malti

Add Comment